Washington and Beijing are poised to agree on a new trade arrangement. Once that deal is done, diplomatic practitioners in both capitals will turn their attention to the rest of the U.S.-China relationship — spanning national security, artificial intelligence, human rights and the overall political situation between the two countries.

Those who follow the dynamics of the U.S.-China relationship closely have carefully analyzed Vice President Pence’s speech last October at the Hudson Institute. It was arguably the most hard-line speech delivered by any U.S. administration against China since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1979. Together with the National Security Strategy of December 2017 and the National Defense Strategy of January 2018, Pence’s remarks marked the end of strategic engagement and the start of a new era of strategic competition between the United States and China. According to the vice president, this would involve a fundamental reset by the United States across all domains of U.S. policy.

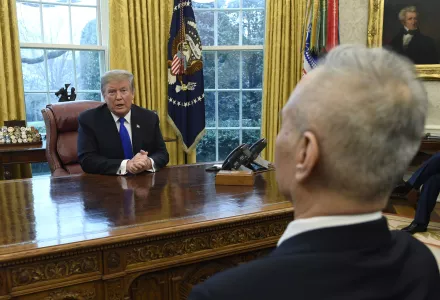

Over the past 12 months, the Trump administration has been busily fleshing out this new policy toward China. What we do not know, however, is what will happen within the administration once the trade deal is signed, sealed and delivered.

The first possibility is that President Trump, having (as he sees it) honored his promise to his political base during the 2016 campaign to secure a “fair deal” for the first time between China and the United States on exports and jobs, will then delegate the details to his subordinates. In this scenario, the national security hawks in the Pentagon, State Department, the National Security Council, and the intelligence community would then be unleashed to implement a comprehensive strategy that seeks to constrain China’s increasingly assertive international behavior.

The alternative scenario is that President Trump, who has stated repeatedly his high personal regard for Chinese President Xi Jinping, will act as a broader “guardian” of the U.S.-China relationship and not allow the hawks in his entourage to prosecute such a robust strategy against Beijing. Trump, it will be noted from the official record, has rarely if ever attacked China over its strategic policies in the wider Indo-Pacific region, including the South China Sea. Nor has Trump addressed China’s broader economic and political challenges to America’s long-term status as the largest economy and largest military power in the world. Nor can we find any record of a public position taken by Trump on China’s human rights record. Indeed, the president has often chosen to equivocate about human rights questions in the broader international diplomacy of his administration. It is therefore entirely possible that Trump, in order to protect the implementation of his bilateral trade agreement with his Chinese counterpart, will choose to keep the rest of his administration in check to avoid damage being done to what he really cares about — American trade and economic interests.

The question of which way Trump will jump in the post-trade-deal world is one of current concern in both Washington and Beijing. Chinese policymakers are understandably anxious about which way Trump will go — and the hawks in his own administration are anxious as well. Xi will be particularly keen to secure maximum leverage over Trump in the wake of the trade agreement — not only to prevent the outbreak of a fresh trade war but also to prevent the United States from gaining advantages in other areas of the relationship. Xi will be especially sensitive to what the Trump administration does next on Taiwan, including future arms sales to the island.

The uncomfortable truth is that the two countries face a deepening divergence of values and interests. The economic and military gap between them is narrowing, and both recognize that their mastery of high technologies of the future (of which artificial intelligence is but one) will ultimately determine their future claims to dominant superpower status. Given these realities, it is difficult to imagine a new bilateral relationship that will be based on policy principles substantive enough to prevent the two countries from gradually sliding in the direction of crisis, conflict or even war.

The bottom line is the U.S.-China relationship remains brittle. There has been little engagement between the two sides over the past two years on the overall foreign and security policy dimensions of the relationship. Little political and diplomatic ballast remains. And both the Trump administration and Xi’s team remain deeply conscious of the fact that, ahead of next year’s congressional and presidential elections, Trump will be facing a Democratic Party eager to attack him from the right on China for any perceived concessions he may make to the Chinese in the critical year ahead.

Rudd, Kevin. “Even a Deal on Trade Won’t Paper Over the Widening Gap Between Washington and Beijing.” The Washington Post, April 24, 2019