Introduction

On February 14, 2024, the Russian Federation announced that it would suspend its annual payments to the Arctic Council “until the resumption of real work in this format with the participation of all member countries.”1 This suspension comes after over two years without in-person Arctic Council meetings. It highlights the importance of carefully examining how the Arctic Council got here, and what opportunities there are for cooperation in the future.

The Arctic Council has long been the central hub for cooperation on Arctic issues. That changed in 2022, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine profoundly shifted Arctic governance dynamics. A week after the invasion, the seven other Arctic Council member states—Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the United States—announced that they were pausing participation in Council meetings. This disrupted the decades-long peaceful cooperation that had persisted between Arctic states, Indigenous Peoples’ organizations (Permanent Participants), as well as a broad range of experts and knowledge holders both in and outside the region.

There have been no in-person Arctic Council meetings since then, but some activities have resumed at the working level. In August 2023, under Norway’s leadership, all eight Arctic states reached consensus to establish new guidelines to allow decisions to be made through written procedures. This enabled some work to proceed without requiring Arctic Council member states and Permanent Participants to convene in-person as a group. While far from ideal, this decision-making process was seen as a way to reinvigorate cooperation in recognition of the many Arctic issues that remain pressing.

Arctic states have been clear that the Arctic Council is still their chosen mechanism for regional cooperation, despite the challenges posed by the war in Ukraine. But charting a path forward for the Arctic Council is not about returning to “business as usual.” Rather, it is about finding ways to advance cooperation based on emerging needs and broader geopolitical dynamics. This report endeavors to inform responses to this crisis moment with key takeaways and practical recommendations for future cooperation.

Present and Future of Arctic Council Cooperation: Key Takeaways

More than two years have passed since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted a pause in in-person Arctic Council meetings. Since then, some work has resumed, particularly at the working level. Workshop participants took stock of the Arctic Council’s progress since the 2022 invasion, and four key trends emerged:

- The Arctic Council Chair’s role has been elevated. The eight Arctic states take turns serving as Arctic Council Chair, and Chairships rotate every two years. In 2023, Norway took over from Russia as Chair and began working to restore constructive cooperation after a tense year with Moscow at the helm. Norway—and future Chairs—have a more complicated role now that in-person meetings have stalled. It is harder to reach the full consensus that is required to make decisions at the Arctic Council because the Chair cannot engage with one collective group of eight states and six Permanent Participants to facilitate decisions. Instead, they must engage bilaterally with each Arctic Council member state, Permanent Participant, and Working Group. The forward motion of the Arctic Council depends on the Chair serving as an effective leader and interlocutor in this environment.

- Indigenous Peoples’ participation is crucial and at risk. Indigenous Peoples have played an integral role in the Arctic Council since the Council’s formation in 1996. Indigenous Peoples’ input, convening power, people-to-people contacts, and cross-border connections are even more crucial now that not all representatives of Arctic states can be in the same room. However, the Permanent Participants are facing new hurdles to their participation. The operating guidelines introduced in August 2023 that allow decisions to be taken in writing instead of in person creates a heavy burden on the human capacity and financial resources of Permanent Participants. These organizations have very few permanent staff that must now review large quantities of written material to determine what information is relevant, what decisions are being proposed, and how and where they would like to engage. All this must be done in relatively short periods of time and with little or no opportunity for discussion about the issues under consideration.

- The Arctic Council is still capable of realignment. Unlike many other international fora, the Arctic Council is not treaty-bound. This absence of formal legal obligations can be an asset during this period of uncertainty because it can enable innovation and flexibility. The Council has adapted before. In 2019, when the prospect of a Ministerial Declaration became impossible, the Finnish Chair mobilized in real time to release a “Statement by the Chair” that acknowledged the Arctic Council’s accomplishments from 2017-2019 and identified key priorities for the incoming Icelandic Chairship.2 Similarly, the “pause” of activities following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a form of realignment driven by necessity. During this period of flux, the Arctic Council has an opportunity for self-examination, discerning what initiatives to prioritize and what processes to improve.

- The Council suffers from a perceived lack of transparency and communication. The current Chair of the Senior Arctic Officials, Morten Høglund, has stressed that “the Arctic Council is not dead,” but how can outside observers really know?3 The Arctic Council has previously been characterized as a “black box,” and the current absence of public information is feeding this reputation and leaving space for others to fill the void. The Arctic Council’s presence on the international stage is also weakened. Visible participation of Arctic Council representatives in international discussions and events is crucial to maintain the Council’s relevance.

How do Indigenous Peoples participate in the Arctic Council?

The most prominent form participation by Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic Council is as Permanent Participants. Six Indigenous Peoples’ organizations—representing approximately 500,000 of the 4 million people living in the Arctic—have been granted Permanent Participant status in the Arctic Council. Their participation in the Arctic Council provides important knowledge and expertise that inform the Council’s activities and decisions and lends the institution credibility. Permanent Participants have full consultation rights in the Council’s negotiations and decisions, which in many cases means that Arctic Council decisions only move forward with Permanent Participant support. The Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat exists to support Indigenous Peoples’ participation in the Arctic Council.

Indigenous Peoples’ organizations can also engage in the activities of the Arctic Council as Observers (e.g. Association of World Reindeer Herders) and as experts and knowledge holders in specific Arctic Council projects or initiatives.

Image: Arctic Council. “Permanent Participants.” Accessed February 16, 2024. https://arctic-council.org/about/permanent-participants/.

Recommendations for Working-Level Cooperation

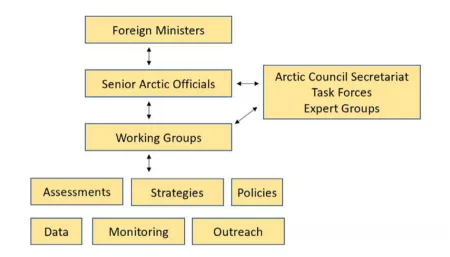

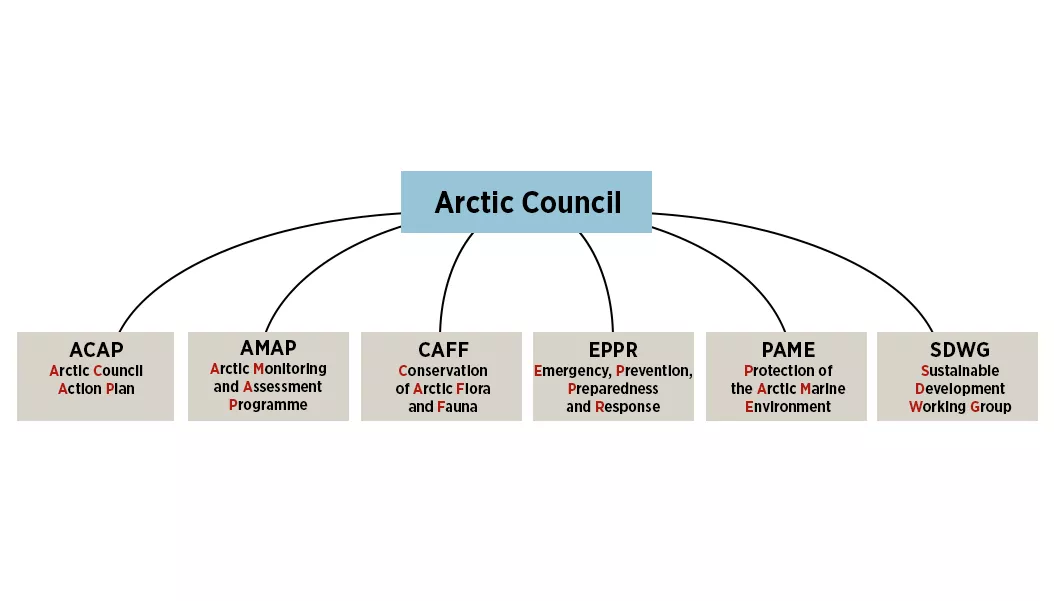

The working level has always been the Arctic Council’s engine, where experts collaborate to execute the Council’s work related to environmental protection and sustainable development. This work is delivered through its six permanent Working Groups and various expert groups and task forces that are created on an “as needed” basis to tackle specific issues or topics. What’s more, the Working Groups and the currently active Black Carbon and Methane Expert Group have the most opportunities to be active under current circumstances.

Promoting working-level cooperation is the best way to preserve the Arctic Council’s efforts to sustain strong Arctic networks and communities of practice and, by extension, advance Arctic issues. Recommendations to strengthen working-level cooperation under current constraints include:

- Allow working-level projects to move forward as long as they align with established Arctic Council priorities and mandates. Currently, projects at the working level can only move forward if they were already in motion before the 2022 pause. This is in large part because the Arctic Council functions on consensus and new projects require Senior Arctic Official approval, which is difficult to attain while in-person meetings are stalled.

However, opportunities could be explored to allow new projects to move forward without formal endorsement. There are several guiding documents that Working Groups and other subsidiary bodies could reference to further their work while ensuring they remain in compliance with Arctic Council priorities and mandates, such as the Arctic Council’s Strategic Plan, Chairship priorities, and Working Group strategic plans. Providing clear and consistent guidance about how Working Group projects can advance would be a promising first step. - Make working-level participation more accessible to Permanent Participants. The requirement that the Arctic Council conduct much of its business in writing increases the administrative burden for all participants. For Permanent Participants, the increased workload of this mode of decision-making stretches capacity to engage meaningfully. Working Groups should pay careful attention to how digestible their written communications are, and, when possible, the Council might consider allowing video communication as an alternative.

One reason Permanent Participant capacity is stretched is they have fewer people and sources of funding than state governments. Improving accessibility for Permanent Participants requires ensuring that they have reliable funding streams so that knowledge holders have the resources necessary to fully participate. - Invest in expert work. At a time when state interaction is less feasible, Arctic states can focus on ensuring that expert-level collaboration continues. The Arctic Council has tremendous convening power and can foster more interdisciplinary collaboration. Cross-cutting teams and consistent expert engagement are necessary to study and respond to current and emerging needs, like the consequences of Arctic wildfires. Providing experts with reliable and sufficient financial resources to conduct their work and engage in Arctic Council activities will also be crucial.

Recommendations to Improve Extra-Institutional Cooperation

There is more to Arctic governance than the operations of the Arctic Council. The Council exists within a network of institutions and, whatever the fate of the Council, Arctic issues can be advanced in a variety of other settings (e.g. Arctic Coast Guard Forum, International Maritime Organization [IMO], and International Conference on Arctic Research and Planning). The Arctic Council can play an important role in strengthening cooperation outside the Council, including:

- Support outside activity that aligns with the Arctic Council’s mission. Some working-level activities will be infeasible at the Arctic Council under current circumstances. However, there are other organizations that could take on these activities. For example, the Arctic Council’s Protection of the Marine Arctic Environment (PAME) Working Group has worked with the International Maritime Organization on the Polar Code, which regulates shipping. More of this activity can be facilitated through the IMO while PAME actions are limited.

- Facilitate indirect information sharing. Recent research suggests that suspending scientific cooperation with Russia adversely impacts scientists’ ability to accurately describe climate change’s impacts on the Arctic.4 While remote sensors can help scientists understand some climate change indicators, ground-based observations have long been the backbone of Arctic climate science. The Arctic Council can help promote common data standards and publishing to facilitate indirect information sharing, including with Russia. This ensures data on things like permafrost thaw and methane emissions can be aggregated in a manner that is less politically charged.

Looking Ahead

The Arctic is a constantly changing environment, and policymakers need to make decisions on Arctic issues with a full understanding of these fluctuating conditions. In the past, the Arctic Council has played a pivotal role in translating scientific discoveries into policy-relevant insights for practitioners. But there is no “right” way to ensure a strong connection between experts and decisionmakers. What matters is that dialogue to develop viable and effective options for the future of Arctic governance continues. Meeting this geopolitical moment with flexibility and innovation provides the best chance to advance Arctic issues and ensure the Arctic Council’s continued relevance.

About the Report

This report is based on insights from a two-day workshop hosted by the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in collaboration with the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, the Center for Ocean Governance at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, and the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center. Participants included representatives from civil society, academia, Indigenous Peoples’ organizations, and governments with knowledge of and experience with the Arctic Council and other regional governance mechanisms. Participants developed practical recommendations for facilitating working-level cooperation through the Arctic Council and other institutions.

Spence, Jennifer and Hannah Chenok. “The Future of Arctic Council Innovation: Charting a Course for Working-Level Cooperation.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, February 20, 2024

- Reuters. “Russia Suspends Annual Payments to Arctic Council, RIA Agency Reports.” February 13, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-suspends-annual-payments-arctic-council-ria-agency-reports-2024-02-14/.

- Gulliksen Tømmerbakke, Siri, and Martin Breum. “First Ever Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting Without Joint Declaration.” High North News, May 7, 2019. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/first-ever-arctic-council-ministerial-meeting-without-joint-declaration.

- Simpson, Brett. “The Rise and Sudden Fall of the Arctic Council.” Foreign Policy (blog), February 22, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/05/31/arctic-council-russia-norway/.

- López-Blanco, Efrén, Elmer Topp-Jørgensen, Torben R. Christensen, Morten Rasch, Henrik Skov, Marie F. Arndal, M. Syndonia Bret-Harte, Terry V. Callaghan, and Niels M. Schmidt. “Towards an Increasingly Biased View on Arctic Change.” Nature Climate Change, January 22, 2024, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01903-1.