The announcement that Canada has officially lost its measles-elimination status is more than a bureaucratic downgrade, it’s a warning.

In November 2025, the Pan American Health Organization confirmed that measles has been circulating endemically in Canada for more than 12 months, the threshold that marks the loss of elimination status. The decision reverberates beyond Canada’s borders. The Americas, once the first region in the world to eliminate measles twice, is no longer measles-free.

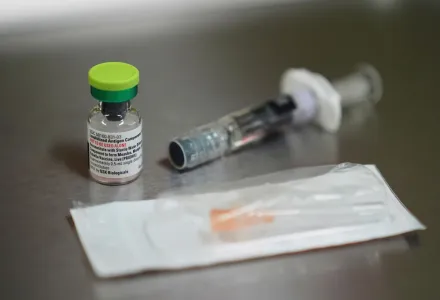

Why does this matter? Because “elimination” is not a trophy; it’s a test of whether a nation can maintain high, equitable vaccination coverage and a vigilant public-health system. Measles is one of the most contagious pathogens known to medicine. With a basic reproduction number (R₀) between 12 and 18, a single case can ignite an outbreak in any community where vaccination coverage dips below roughly 95%. Canada achieved elimination in 1998 by meeting that standard.

But coverage has since slipped. Across the Americas, regional measles–MMR vaccination rates dropped to about 79% in 2024. Canada has now logged more than 5,100 cases this year, including two infant deaths. The outbreak, which began in late 2024, has persisted across multiple provinces, largely among under-vaccinated communities.

This is not just a Canadian problem, it’s a red flag for every high-income country that believes strong health systems alone can hold the line. Elimination, once lost, exposes the cracks that have widened quietly over time: misinformation, inequities in access, waning public trust.

The United States could be next. America declared measles eliminated in 2000. Yet as of early November 2025, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has confirmed 1,681 cases, the highest number in more than 30 years. Two-thirds of those infected are children and adolescents, and 92% are unvaccinated or of unknown vaccination status.

Researchers at Stanford and elsewhere warn that if vaccination rates continue to stagnate or decline, measles could re-establish endemic transmission in the U.S. within two decades. The same conditions that reignited measles in Canada, under-vaccinated clusters, overburdened surveillance systems, and travel-linked importations, are present here too.

To avert that future, the U.S. must act decisively.

First, close immunity gaps, target communities with low coverage, not just raise national averages.

Second, strengthen surveillance and outbreak response, detect cases early, confirm them rapidly, and trace contacts before transmission spreads.

Third, rebuild vaccine confidence, combat misinformation and rebuild trust through credible messengers and community partnerships.

And finally, commit sustained political and financial support, because elimination is fragile when complacency sets in.

Canada can regain its measles-free status once the current outbreak is extinguished, after at least 12 consecutive months of confirmed interruption of transmission, verified by robust vaccination, surveillance, and outbreak-response data.

That must be our shared goal across borders. Measles elimination is not a one-time victory; it is a continuous obligation. The virus moves fast, exploits doubt, and punishes neglect. The time to act, for Canada, for the United States, and for the region, is now.