Setting the Stage

On February 21, the "Cooperation or Conflict in the Arctic: What to Do About Russia During a Climate Crisis?" study group met for the second time. Arctic Initiative Senior Fellow Margaret Williams moderated a panel of guest speakers representing different fields of expertise: marine biologist Masha Vorontsova; marine mammal biologist Vladimir Burkanov; research scientist and professor Sue Ellen Moore; quantitative ecologist Eric Regehr; marine policy analyst Inga Banshchikova; and environmental activist and journalist Evgeny Simonov.

The following post summarizes key learnings.

The War in Ukraine and the Environment

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has devastated Ukraine’s natural environment and the health and well-being of its citizens, but the war’s impacts have not been limited to Ukraine. A panel of guest experts joined the study group to discuss the war’s direct and indirect environmental effects in the Arctic: the freeze in Western-Russian science cooperation, the repression of environmental organizations in Russia, and heightened risk of environmental disaster along the Northern Sea Route, a shipping route which traverses Russia’s Arctic coast and passes through the Bering Strait.

The War's Environmental Impacts on the Ground in Ukraine

Wars have profound and lasting negative impacts on human health and well-being, as well as on the natural environment. The widespread use of weapons and machinery during conflicts leads to deforestation, soil erosion, and habitat destruction. Additionally, the release of toxic chemicals and pollutants, as well as the burning of fossil fuels, contribute to air and water pollution, contaminating life support systems for people, destroying ecosystems, and endangering wildlife. The long-term consequences of war on the environment can persist for decades, affecting not only the health and well-being of human populations but the natural world. Although today’s panel did not discuss these particular subjects, it is Russia’s unjust and brutal war on Ukraine – now in its second year - that creates the context for this discussion. For extensive coverage of the war’s impacts on Ukraine’s natural heritage, visit the Ukraine War Environmental Consequences Work Group.

Most cooperation between the West and Russia on conservation and research has been put on hold in the Arctic, but Indigenous organizations have some flexibility.

Since Russia’s invasion on February 24, 2022, most forms of collaboration between Russia and the other Arctic countries have halted - and with it, fruitful, decades-long cooperation on biology and nature conservation research. The flow of data across boundaries has stopped, making it nearly impossible to understand how wildlife and ecosystems are shifting at a time of rapid and extreme temperature increases in the Arctic. Understanding how humans will be impacted by massive environmental change, such as permafrost thaw (which contains 2.5 times more carbon than that which is already in the atmosphere), will be severely hampered without communication across the entire Arctic.

The necessity of working across political boundaries to fully understand Arctic ecosystems was highlighted by some of our panelists. For example, one scientist described an opportunity in the early 1990s to be part of an international expedition that traversed the maritime boundary from Alaska into Russian waters of the Chukchi Sea. Before this experience, the boundary had once served as a curtain, preventing a clear view of the entire ecosystem. The expedition was revelatory, as she and other biologists could see first-hand how completely different the ecology and physical oceanography are in the western Chukchi from the eastern Chukchi.

Similarly, another scientist spoke of the importance of collaboration across boundaries to study polar bears. In this case, the Agreement on the Conservation and Management of the Alaska Chukotka Polar Bear Population established a mechanism not only for scientists to work together but for Alaska Native people and Indigenous Chukchi to participate in research and management, including through the setting of harvest quotas.

Indeed, this agreement highlights the role of Indigenous communities in working across political boundaries. Other examples mentioned include the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and the Alaska Walrus Commission, which have maintained connections to Indigenous hunters and subsistence whaling communities in Chukotka, Russia.

The panelists also touched on the importance of other forums for Arctic cooperation. In the case of polar bear research, although bilateral communication has stopped and implementation of the Alaska-Chukotka polar bear agreement is stalled, another venue has made possible the continuation of some information exchange. This is the Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears, a multilateral treaty signed in 1973 by the five nations where polar bears are found: Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway (Svalbard), the United States, and the Soviet Union. Through this multilateral agreement, scientists are still communicating about the circumpolar status of this iconic and climate-imperiled species.

The Arctic has witnessed 30 years of very open collaboration, with people from many countries trying to address similar challenges and questions regarding shared Arctic species and ecosystems. Continuing – or, more accurately, reviving – this tradition in the Arctic will be important to gain a full understanding of what is happening as Arctic systems continue to be transformed by rapid and acute climate change.

Major challenges hinder collaboration, including prohibitions for federal employees in western countries to work with Russian counterparts. And for Russian scientists, exchanging information can be unsafe. In order to resume the once-fruitful collaboration in the future, it will be essential to preserve existing connections. Even if data exchange is on hold, maintaining personal relationships among researchers can help to keep those communication channels intact. The presence of many skilled Russian biologists now in other countries is an opportunity for western scientists to continue collaboration and communication.

Civil society, once a force for protecting clean water, air, land, and wildlife, is now crippled in Russia.

Russia’s environmental protection structures have changed in multiple ways since President Vladimir Putin took office in 2000 and dissolved the Ministry of the Environment. Increasingly, economic interests, including the extraction of timber, oil, and gas, have gained primacy over nature conservation and research in Russia.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have paid the price, especially in the last two years, as many environmental NGOs have been designated as “foreign agents” in Russia, forcing groups to close their offices, lay off staff, and halt their work. International organizations such as WWF and Greenpeace have been designated “undesirable organizations” and are unable to continue their work in Russia. Both of these are examples of NGOs which for many years complemented governmental functions, for example by funding protected areas, organizing training seminars supporting wildlife research, and monitoring wildfires and oil spills. By effectively stamping out the conservation movement, the Ministry of Justice in Russia has created a massive void in protection and management of habitat and wildlife, and of oversight and enforcement for resources such as timber and fish stocks that require careful management.

The repression of civil society has a cost for Russian nature, but the study group was reminded that even in 2022, a public outcry across the country in reaction to the use of Wrangel Island Nature Reserve for military exercises led to the end of the practice. However, for the most part, Russian NGOs are now severely restricted.

Civil society outside of Russia, however, remains active, documenting the impacts of the war in Ukraine as well as its reverberating effects far beyond Ukraine’s boundaries.

Western sanctions on Russia have accelerated a trend of increasing shipping and resource extraction along the Northern Sea Route.

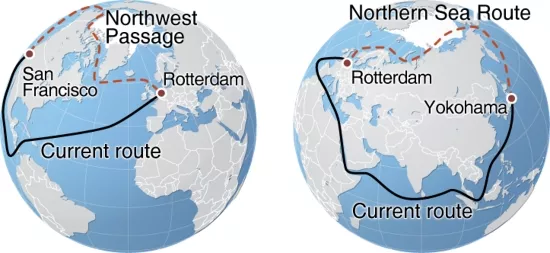

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is a maritime shipping route that traverses the Arctic Ocean along the northern coast of Russia. This route extends from the Barents Sea (off the coasts of Russia and Norway) to the Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska, offering a significantly shorter passage between Europe and Asia compared to traditional shipping routes such as the Suez Canal.

Receding Arctic sea ice due to climate change has made the NSR increasingly accessible, leading to growing interest from shipping companies and governments seeking to exploit its potential for faster and more cost-effective transportation of goods. However, the route presents significant challenges, including harsh and unpredictable conditions as well as limited emergency response infrastructure, necessitating careful navigation and cooperation among Arctic nations to ensure safe and sustainable shipping operations.

Additionally, the opening of the NSR raises concerns about the environmental impacts of increased ship traffic, including air and water pollution, disturbance to wildlife and fragile Arctic ecosystems, collisions with small watercraft and marine mammals, and the potential for oil spills, which would have lasting impacts on marine life and coastal communities.

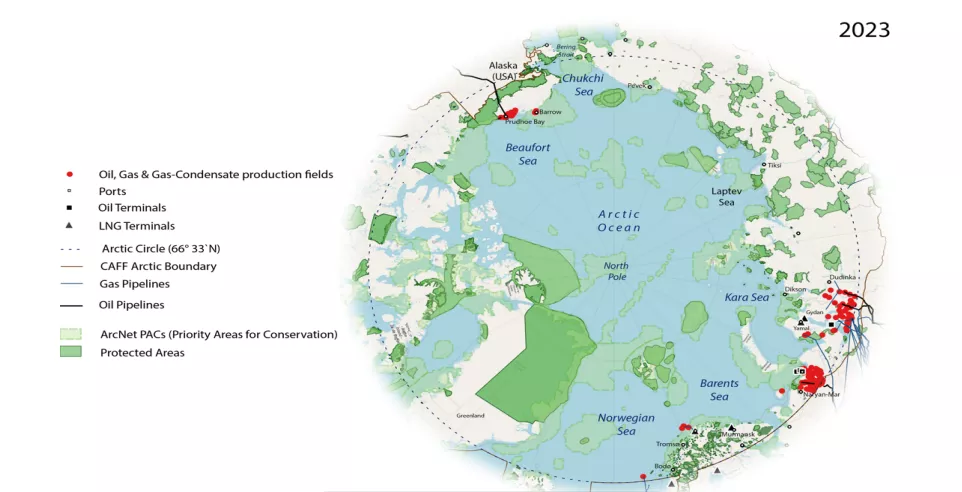

Even before 2022, Russia was promoting economic investment along the NSR. Since the war in Ukraine and the subsequent withdrawal of Western companies from the region, Russia has looked toward Asia for new partnerships. The growth in ship traffic shows that this strategy has thwarted the West’s efforts to hurt Russia economically. Although the numbers of vessels using the NSR are still small compared to the Suez Canal, in 2023 shipping activity increased along the route by 40%. Furthermore, Russia has already reaped $600 billion in profits for fuel exports – facilitated by the NSR – and plans to significantly expand extraction of fossil fuels in its Arctic territory. In 2023, 91% of Arctic-sourced oil exports came from Russia. Russia is pushing heavily to accelerate development along the NSR through tax cuts and economic policies to incentivize investment.

Liquified natural gas (LNG) is also a major source of income for Russia. LNG exports are not covered by European sanctions and today half of Russia’s LNG is going to Europe, particularly Spain, France, and Belgium. Russia plans to nearly triple its LNG export capacity by 2030.

After Western companies stepped away from Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, Asian companies have filled the gap. In 2023, a record volume of cargo was transported along the NSR. The rush to extract minerals and hydrocarbons in the Arctic along the NSR, coupled with Western sanctions on non-LNG products, has pushed Russia to find new business partners in Asia. The last two years have witnessed notable growth of many new projects between China and Russia. The vast majority of crude oil sourced in the Arctic is produced by Russia and mostly transported to China. China registered 123 companies to operate in the Russian Arctic in 2023 alone.

On a slightly positive note for the natural environment, an existing U.S.-Russia agreement on responding to oil spills in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas provides a mechanism for a joint approach to such an incident. However, in the Bering Strait region, the acute lack of infrastructure to support oil spill response, and the unpredictable ice conditions create a heightened ecological risk at a time of growing transport of hydrocarbons through this area. Furthermore, the breakdown of bi-lateral cooperation also has put a stop to communication between U.S. and Russian emergency response personnel who, before the war, had been in regular contact.

Consequences for Conservation When Collaboration Turns to Conflict

The panel delivered a powerful case for how U.S.-Russia collaboration over three decades contributed to the world’s understanding of Arctic species and ecosystems. The opportunity to hear directly from biologists who have worked on both sides of the U.S.-Russia maritime boundary offered a unique glimpse into the a-political nature of wildlife. Yet the current situation also demonstrates the capacity for geopolitics to upend years of progress in researching and protecting wildlife.

While a number of articles in science publications have highlighted the negative impact of interrupted communication with Russia on climate research, less attention has been given to how biodiversity research and conservation are impacted by the war. Of course, as troubling as these developments are for the Arctic, we cannot forget the devastating environmental impacts of the war in Ukraine.

Williams, Margaret. “The Environmental Impacts of the War in Ukraine in the Arctic.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, March 4, 2024