Intelligence expert says both seek to topple U.S. from atop world stage, with Beijing’s blend of money, influence, all-hands-on-deck approach posing bigger threat.

The decades-long battle between Western intelligence services and the Soviet Union offers important lessons for the ongoing national security threat posed by Russia under President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer, and for the rapidly emerging threats from 21st-century China, according to a new book.

"Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West," written by Calder Walton, assistant director of the Intelligence Project and the Applied History Project at Harvard Kennedy School, examines the Soviet intelligence program that was for decades more aggressive and often, more sophisticated than the West's. As the just-released film "Oppenheimer" reminds us, even the top-secret U.S. effort to build the atomic bomb during World War II was compromised from the start by Soviet spies, who eventually delivered those plans to Josef Stalin.

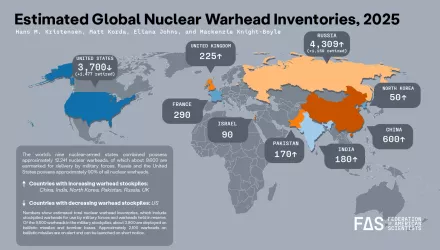

Today, U.S. and U.K leaders agree that China represents the greatest intelligence threat to the West. Chinese hackers are suspected of accessing email accounts of the U.S. State and Commerce departments in June (including that of U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns, a former HKS faculty member), and U.S. officials also believe they planted malware in networks controlling power, water, and communication at military bases. Those incidents, along with the discovery of a Chinese spy balloon hovering over U.S. military sites earlier this year, provide an insight into what Walton calls an "epic intelligence war" beginning between China and the West. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Calder Walton

GAZETTE: Almost at every juncture, Soviet intelligence seemed to be a few steps ahead of U.S. and British intelligence services in the 20th century. Why was the West often caught so flat-footed?

WALTON: You're absolutely right. Western services, certainly the British and the Americans, were really flat-footed at key strategic moments, looking the wrong way or consumed by other threats. The Soviet Union last century, and Russia today, have viewed Western powers and these two countries in particular, as a continuous threat — even when relations ostensibly improved.

We saw this during the Second World War, when the Soviet Union was, at least ostensibly, allies with Britain and the United States. Stalin, of course, never viewed the Western allies in the same way we did him, never as a true ally. This was equally the case during détente, the thawing of relations in the 1970s; it was certainly the case in the 1990s, and then, the post-9/11 period, during the war on terror.

Why is this? Ideological animosity explains much of the Bolshevik Communist attitude toward the Western powers. The U.S., in the 1920s and '30s, was standing outside of world politics. Britain's intelligence services were at least aware of the pervasive threat posed by Soviet intelligence, but just had shockingly small resources. The U.S. didn't have a peacetime intelligence service until 1947, when the CIA was created. Talk about being late to the intelligence game: All the other leading world powers, by that point, had dedicated foreign intelligence agencies, and the U.S. did not.

In 1929, Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson infamously closed down the U.S. government's dedicated code-breaking "black chamber" on the grounds that, he said, this was an "impolite" thing to do and that "gentlemen do not read other's mail." That kind of attitude displayed a deeper sense of naiveté with successive White Houses when it came to intelligence generally, but Soviet intelligence, in particular.

GAZETTE: Theft of U.S. atomic bomb plans was a major triumph for Soviet intelligence. And while Robert Oppenheimer was not a Soviet spy, many key figures in the Manhattan Project were. What did you find in your research?

WALTON: The MI5 dossier on Oppenheimer is declassified, and I studied it while writing the book. Oppenheimer didn't have a British connection — he studied in Cambridge briefly, as the movie shows, but there wasn't much in the dossier in terms of British direct involvement. But what it does contain is liaison reports with the FBI, so it gives us a bird's-eye look into what the FBI was saying about Oppenheimer at the time. I'm relying heavily on the research of two scholars, John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr. They're the ones who have done the most forensic analysis of Soviet intelligence operations and the Manhattan Project.

Looking at British and FBI dossiers, what we find is just how heavily Soviet intelligence services penetrated the Manhattan Project. Klaus Fuchs, a German émigré scientist who did groundbreaking research on the theoretical side of the atomic weapons, was a Soviet spy from the outset when he joined the British atomic bomb project and then, when Roosevelt and Churchill decided to set up a joint atomic bomb project, Fuchs was transferred over to Los Alamos. He was a spy throughout. Other Soviet spies include [1944] Harvard graduate Theodore Hall — he was a Communist true believer. Fuchs and Hall, at the end of the war, after the Trinity test, delivered the plans for the atomic bomb. They didn't know about each other, of course, but separately disclosed the plans to their Soviet handlers. Ted Hall copied the plans of the atomic bomb onto a newspaper using milk. That gives you an insight into the level of espionage.

Another example that has recently come to light is George Koval. He was an American chemical engineer who gave valuable intelligence on the mechanism for initiating the atomic bomb from a laboratory within the Manhattan Project in Dayton, Ohio. His name has been known, but the true level of espionage was not revealed until he died at the age of 92. In 2007, Putin gave him a posthumous honor and praised him with a champagne toast saying the mechanism used in the Soviet Union's first atomic test in 1949 was made according to a "recipe" delivered by Koval.

All of this espionage guaranteed that when the Soviet Union detonated its first weapon in 1949, it was a replica of that developed at Los Alamos and dropped on Nagasaki.

From my perspective, Los Alamos represents the greatest security breach in modern U.S. history. And, by implication, constitutes the greatest Soviet intelligence success, probably the greatest espionage success in history. The delivery of plans to the Soviet Union accelerated the Soviet atomic bomb project....

Pazzanese, Christina."Lessons for Today's Cold War 2.0 with Russia, China." Harvard Gazette, August 8, 2023.

The full text of this publication is available via Harvard Gazette.