In any case, Jakarta policymakers are interested in boosting Indonesia’s nickel competitiveness by involving

both the United States and China, including through collaboration in infrastructure development. However,

they are not yet seeking to do so through better policy alignment between the two superpowers. Without

directly engaging the United States and China in a trilateral format over their exclusionary competition,

it would be difficult to persuade both countries to collaboratively invest in Indonesia’s nickel industry. If

Indonesia chooses, it could leverage and scale past experiences, such as the joint venture between U.S.

automobile manufacturer Ford, China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, and PT Vale Indonesia in a $4.5 billion

nickel-processing plant.

More broadly, Indonesia could engage both China and the United States through green technology. Given

both countries’ interest in the green transition, Indonesia could strengthen its leverage through its significant

potential for renewable energy development, such as solar, wind, and geothermal power. It could also entice

green technology investments from the United States and China through fiscal incentives and favorable

regulations, with an added boost if the two countries agree to collaborate on specific projects. Furthermore,

Indonesia could also propose a trilateral collaboration to integrate battery and renewable energy supply

chains, developing a robust supply network from raw materials, like nickel, to finished products, like electric

batteries, with each stage prioritizing environmentally responsible practices. Finally, Indonesia could develop

a regional renewable energy research center with involvement from both countries, establishing the country

as a regional hub for renewable energy innovation in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia’s growing role in the global green transition is often associated with its leadership in nickel and

electric vehicles. But this position alone is insufficient. A serious green energy strategy must go beyond

minerals and manufacturing. The country has substantial potential in solar, wind, and geothermal power.

Scaling up these sectors will require greater investment, stronger regulation, and the ability to attract

co-financing not just from China and the United States but also from other middle powers with shared

interests in energy resilience and low-carbon development.

At the regional level, Indonesia could lead by example. Establishing a Southeast Asia renewable energy research

center, for instance, would allow it to pool regional expertise, mobilize financing, and push innovation in clean

energy technologies. Additionally, it would provide a diplomatic opportunity. At COP29, Indonesia took the

initiative in rallying developing countries to demand greater climate finance. That momentum should not be

wasted. By convening middle power platforms on climate diplomacy, Jakarta could help press Washington

and Beijing toward higher ambition, while also positioning itself as a credible broker for technology transfer

and global cooperation. In short, Indonesia’s green leadership will depend not only on its mineral reserves

but on its ability to build institutions, forge partnerships, and shape the competitive dynamics between the

United States and China.

Health and Technology

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, Indonesia was instrumental in establishing and maintaining the Pandemic

Fund during its G20 presidency in 2022. The fund aims to improve global preparedness and response to

future pandemics by combining financial resources from member countries and international organizations.

Hosted by the World Bank with technical support from the World Health Organization, it seeks to help lowand

middle-income countries with pandemic prevention, readiness, and response in disease monitoring,

laboratory infrastructure, and workforce development. In addition to campaigning for this project within the

G20, Indonesia provided financial and diplomatic support, encouraging other countries to commit resources.

While the Pandemic Fund exemplifies Indonesia’s greater commitment to global health security, it could also

serve as a forum for the United States and China to collaborate on the joint goal of building health resilience.

This role strengthens Indonesia’s image as a responsible global health leader capable of bringing together

the United States and China. Its longstanding nonaligned foreign policy and balanced relationships with both

nations allow it to frame pandemic cooperation as a global humanitarian necessity rather than a geopolitical

competition. Multilateral platforms like the fund can facilitate tangible collaborative efforts, such as joint

pandemic preparedness funds, shared vaccine research, and equitable global distribution mechanisms. By

emphasizing the transnational nature of pandemics and mutual vulnerabilities, Indonesia can shift the focus

toward shared interests and meaningful dialogue between the United State and China.

Similarly, in the geo-technological competition between the United States and China, Indonesia should

avoid taking sides and encourage both countries to develop collaborative investments. For example, in the

development of 5G networks and the Internet of Things, Indonesia could allow both Huawei from China and

U.S. technological companies to contribute, subject to strong data security and privacy safeguards. Through

its leadership in ASEAN, Indonesia could also support regional technology initiatives, such as the ASEAN

Digital Economy Framework, which seeks to boost the technological autonomy of member countries through

collaboration. By becoming a regional technological cooperation hub, Indonesia could elevate ASEAN’s

strategic value in the eyes of both the United States and China. It could further encourage U.S.-China

collaboration through ASEAN in areas including cybersecurity and data infrastructure, building its reputation

as a tech development hub in Southeast Asia.

Still, Indonesia’s growing reliance on Chinese and U.S. technology firms poses a quiet strategic challenge.

From cloud infrastructure to 5G networks, the country’s digital backbone is increasingly shaped by external

actors. To preserve strategic room to maneuver, the country cannot afford to be overly dependent on any

single source of technology. The first step is regulatory: all foreign tech investments must meet clear

cybersecurity and data governance standards. But regulations alone are not enough. Indonesia also needs

to build domestic capacity — by supporting local tech startups, expanding STEM education, and building

an innovation ecosystem that allows domestic firms to grow. Diversifying suppliers through partnerships

with Japan, South Korea, and the EU will further reduce vulnerability and promote more open, interoperable

systems. The goal is not autarky but resilience, ensuring that Indonesia has the tools, talent, and choices to

chart its own course in a world increasingly shaped by digital competition.

Converting Passive Assets

The major challenge for Jakarta does not begin and end with exploiting the competitive dynamics between

the United States and China. Not only could such impulses incentivize policymakers to sit back and watch

the competition unfold, encouraging strategic complacency, but they could also undermine Indonesia’s ability

to mitigate future risks driven by geopolitical competitive pressures. While there are few platforms for trade

coordination between Indonesia, China, and the United States — especially given the Trump administration’s

focus on trade deficits and tariffs — Indonesia could still facilitate broader diplomatic mechanisms under

which those issues could be discussed.

An active alignment posture would require Indonesia to better manage its diplomatic ties while directly

engaging with and seeking to shape the U.S.-China strategic competition. For instance, Indonesia could offer

a trilateral platform for the United States, China, and itself to debate regional strategic concerns. This could

take the form of an annual meeting where government officials, firms, and non-government experts debate

trade and investment regimes as well as industries such as nickel, renewable energy, and digital technology.

The forum might also address topics including maritime security, energy transition, health, and infrastructure

development.

Indonesia could further consider coordinating trilateral agreements around policy and norms, such as

establishing criteria for ecologically responsible investments, worker rights, and sustainable corporate

practices. This could extend to legislation governing safe technological transfer. For example, Indonesia

could offer a trilateral meeting to discuss mutually acceptable technology standards, such as 5G deployment

and AI. The platform could also facilitate discussions about sustainable development, focusing on green

projects involving all three countries. By proposing such a forum, Indonesia could create a communication

channel that allows the United States and China to engage on matters of mutual interest while maintaining

its foreign policy independence.

Additionally, Indonesia could strengthen its leadership in ASEAN, leveraging its related mechanisms,

especially the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and East Asia Summit (EAS), which includes the United States

and China, to gradually enhance norms of crisis management and build confidence. The ARF, for example,

has been working on measures related to regional security architecture and preventive diplomacy. However,

the forum has languished in strategic irrelevance, prompting ASEAN foreign ministers in early 2025 to

formulate ways to “revitalize” it. One potential approach is to directly involve the United States and China

in developing built-in crisis management mechanisms on major security flashpoints such as the South China

Sea or the Taiwan Strait. Similar initiatives could institutionalize the EAS beyond an annual gathering of

regional leaders reading pre-prepared statements.

Taken together, this analysis suggests how Indonesia can convert its passive assets —geography, resources,

economic potential, and diplomatic leadership — into an active alignment posture. This posture does not treat

the U.S.-China competitive dynamics as fixed; rather, it is open to influential middle powers like Indonesia.

Active alignment includes both direct and indirect approaches, encouraging Indonesia to not only seek direct

benefits from the United States and China through separate bilateral arrangements but to engage in trilateral

policy coordination across multiple platforms. In other words, Jakarta could encourage the United States and

China to “hang together” with Indonesia rather than to “hang separately.” Achieving this outlook, however,

requires Jakarta policymakers to go beyond exploiting the U.S.-China competition by actively bringing both

major powers to the table.

Conclusions and Recommendations: Promises and Perils of Reforms

Foreign policy begins at home, and conversion of passive assets into active capital to shape the U.S.-China

competition largely depends on domestic economic, defense, and diplomatic reforms in Indonesia. Without a

credible investment climate, Indonesia will struggle to attract the kind of diversified foreign direct investment

that lends economic weight and diplomatic flexibility. Simplifying licensing, improving infrastructure, and

ensuring policy consistency are not just matters of economic reform — they are tools of strategic positioning.

The same logic applies to defense. A credible security posture requires more than procurement; it demands

personnel overhaul, institutional reforms, innovative doctrine, and a realistic budgeting process. Without

it, Indonesia will continue to punch below its weight in shaping maritime norms and responding to regional

security challenges.

Diplomatic capacity is equally essential. An active alignment posture, which engages both major powers

without being beholden to either, requires a foreign ministry that is professional, well-resourced, and

strategically oriented. That means investing in people, not just processes, to shape strategic outcomes.

The challenge is not merely crafting elegant statements or hosting multilateral events; it is about sustained

engagement, deep policy work, and the institutional memory to manage long-term relationships. These

reforms are not peripheral — they are central. Without them, Indonesia will be forced to react to great power

moves rather than help set the terms of engagement.

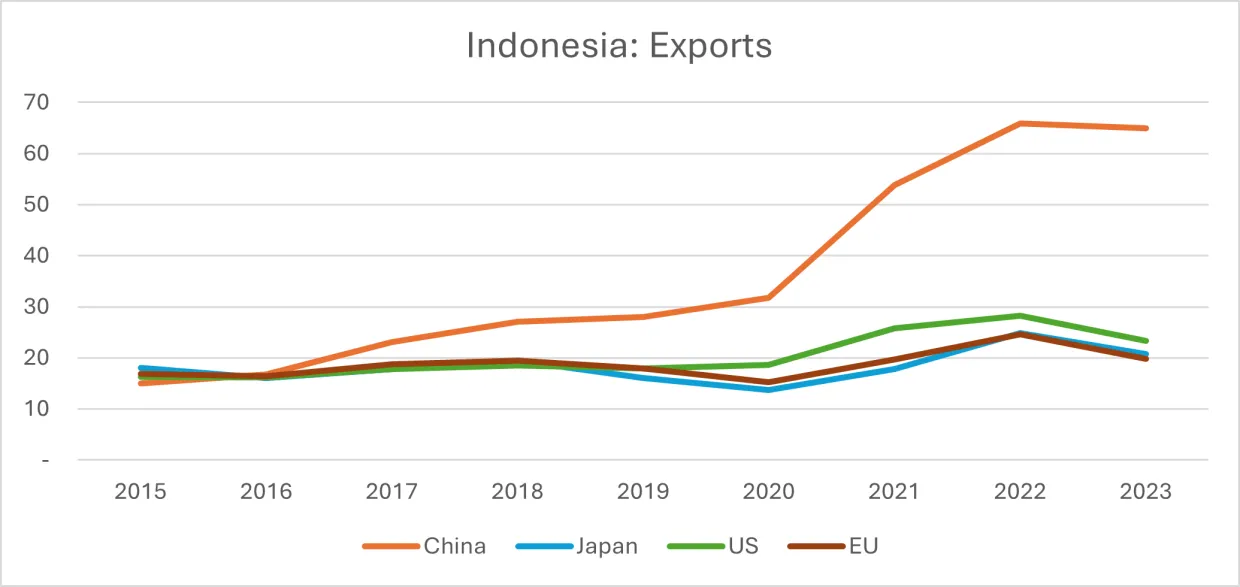

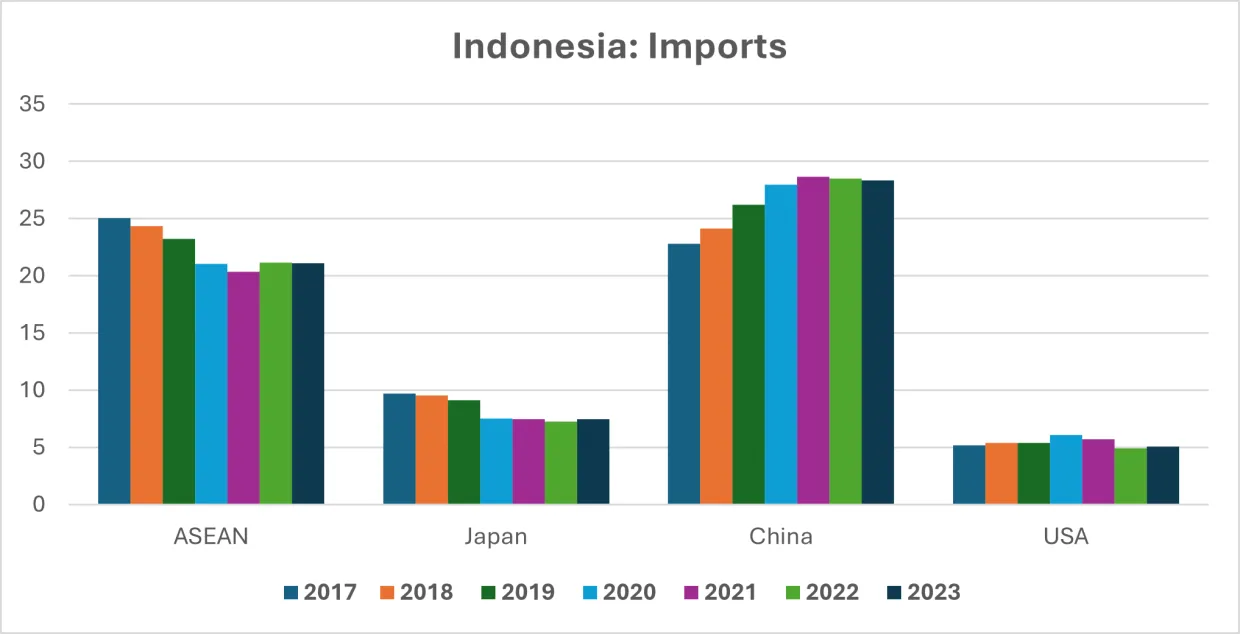

In the economic realm, three broad directions of travel are required. First, Indonesia must become a regional

economic powerhouse to negotiate effectively with the United States and China and encourage collaborative

policy alignments in the areas discussed above. To do so, Indonesia needs to increase its economic growth

from 5% to 7% or higher. Achieving this requires improvements in productivity through advances in human

capital, export growth, and foreign direct investment. Exports must also be diversified in terms of product

types and destination nations. Countries with a mix of medium- and high-tech manufacturing tend to

experience decreased export volatility, while natural resource-rich countries like Indonesia experience

greater volatility. Industrialization is therefore essential to increase Indonesia’s economic complexity, which

remains low compared to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand.

Another area required to boost productivity is export diversification, though it necessitates innovation

underpinned by robust research and development (R&D). Unfortunately, Indonesia’s R&D efforts have

lacked government support and proven ineffective. Offering tax breaks for R&D and workforce training

across industries and emerging technologies could bolster domestic innovation. High shipping costs, which

lower profitability and disincentivize product development, highlight the need for improved infrastructure

and logistics. Innovation also requires high-quality human capital, so Indonesia needs an industrial policy

that promotes skills development and R&D. This could be a challenge, however, given rising levels of youth

unemployment, particularly among vocational high school graduates. Policies that encourage companies to

train and upskill their workers, such as double tax deductions for qualifying programs, could help address

this while building a stronger workforce.

Second, Indonesia needs to enhance domestic savings and boost government savings, requiring tax

administration reforms. Third, Indonesia must develop public policies, such as simplified licensing and

better infrastructure, to encourage investment from other partners beyond the United States and China,

including Japan, the European Union, and Middle Eastern countries. Specifically, encouraging export-oriented

foreign direct investment will generate foreign currencies, so when gains are repatriated, there will not be

pressure on the balance of payments caused by currency mismatches. This could stimulate economic growth

without jeopardizing Indonesian Rupiah stability. Taken together, these economic reforms around growth,

savings, and diversification could allow Indonesia to better implement an active alignment posture vis-à-vis

the United States and China.

But economic progress alone is insufficient to give Indonesia the leverage needed to help bridge the

gap between the United States and China. The country must also consider reforms in defense capability

development and diplomatic management. On defense, Indonesia remains an inconsequential military

power in the Indo-Pacific. Roughly 70% of the military’s operational history since 1945 has been geared

toward internal security and domestic operations. Its combined military exercises scenarios have not

been substantially updated since the 1990s, and its international experience has largely centered on United

Nations Peacekeeping missions, with only a few expeditionary operations against pirates over the past two

decades. Its annual defense budget has rarely reached 1% of GDP, and most of the military’s equipment

is more than three decades old on average. The armed forces continue to deal with various pathologies,

including personnel mismanagement, doctrinal stagnation, education and training lethargy, and archaic

defense planning systems.

Without a massive and fundamental overhaul of Indonesia’s defense capabilities, Indonesia lacks the

credibility to convince both China and the United States that it is ready to assume greater regional security

responsibilities, let alone complicate the conflict risk calculus of both Beijing and Washington. Until then,

convincing Beijing and Washington to collaborate on peacefully managing regional security flashpoints will

be almost impossible. Similarly, Indonesia’s diplomatic leadership in ASEAN will rely primarily on historical

precedent and normative ideas rather than greater capabilities and commitment. Only by showing a

willingness to defend and commit resources to shared regional interests can Indonesia command regional

followership. For the time being, Indonesia’s defense sector is largely focused on its arms procurement efforts

that Prabowo began when he was former president Jokowi’s defense minister. Broader defense structural

challenges are given hardly any consideration beyond procurement, and even those efforts face significant

risks and impediments beyond funding shortfalls.

Finally, Indonesia needs to overhaul its diplomatic capabilities, including its foreign ministry. Under Jokowi

and former Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi, the foreign ministry became unhelpfully focused on processoriented

policies rather than path-breaking initiatives to achieve strategic outcomes. Whether in the case

of the U.S.-China competition, maritime security, or the post-coup conflict in Myanmar, Indonesian foreign

policy has largely become an exercise in producing “reference point” documents without meaningful

strategy. What’s more, under Prabowo’s larger-than-life personality, the foreign ministry has struggled to

support Foreign Minister Sugiono, a Prabowo political party official and former staffer with no diplomatic or

foreign policy credentials. The ministry’s budget has also seen little growth in over a decade, and its regional

and global credibility are on precarious ground due to lack of resources, strategic vision, and follow-through.

Bridging the gap between the United States and China requires a solid foreign policy team to support

Prabowo’s diplomatic impulses to engage in major international events or personal meetings with key global

leaders. Stagecraft, after all, is not statecraft in world politics. It also requires a revamped foreign ministry

less constrained by bureaucratic processes and more aware of geopolitical shifts. Equally important, Prabowo

must heed the advice of professional diplomats who have decades of experience navigating key foreign policy

issues, such the South China Sea. Diplomatic reform therefore encompasses the economic and defense

reforms necessary to convert Indonesia’s passive assets into active capital that can influence the U.S.-China

strategic competition.

In the short term, Indonesia can move quickly by convening trilateral maritime dialogues or advancing ASEAN

digital initiatives. These are low-hanging fruits: practical, visible, and politically manageable. While they will

not change the strategic landscape overnight, they can signal intent and help Indonesia carve out a more

active role in shaping regional norms. Achieving medium- and long-term goals will be harder. A U.S.-China-

Indonesia trilateral summit, for instance, would be ambitious — not just diplomatically but symbolically. It

may not happen tomorrow but planting the seed matters. Structural reforms in defense and foreign policy

will take even longer, requiring political will and institutional follow-through. But even incremental progress

on these fronts sends a message: Indonesia is not just reacting to global dynamics but willing to shape them.

Leadership, after all, is not just about outcomes. It’s about showing up with ideas and the capacity to act.

What do the United States and China expect from Indonesia? Quite simply, they see it as a swing state in

an increasingly contested region. Washington wants alignment on regional security and digital standards,

especially in areas like cybersecurity and 5G infrastructure. Beijing, on the other hand, is focused on market

access and infrastructure investment, from ports to industrial parks. Both are watching closely when it comes

to critical minerals, defense procurement, and broader foreign policy signals. This puts Jakarta in a position

of leverage — but only if it knows how to use it.

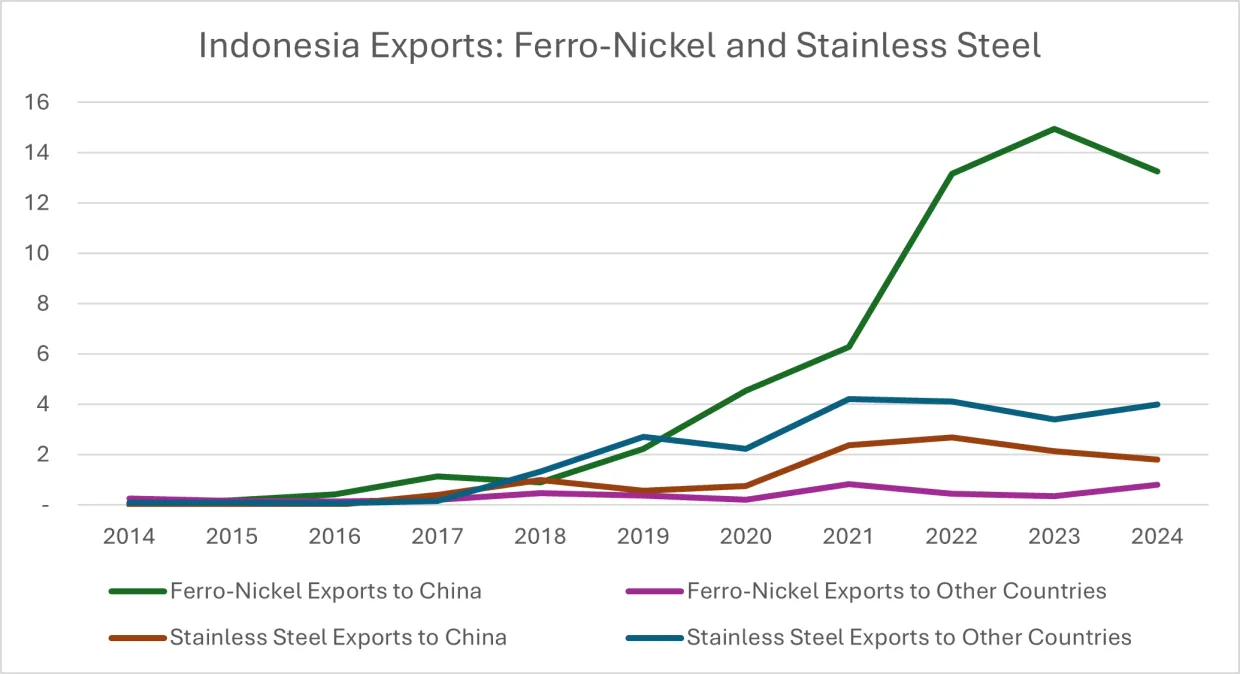

Indonesia can, and already has, benefited from the strategic rivalry between the two powers. Trade diversion in

sectors like nickel, investment competition, and the push for tech localization have opened new opportunities.

But influence is not automatic. It requires clarity of purpose and follow-through. Initiatives like the Pandemic

Fund and the JETP show that Indonesia can help shape international norms when it brings ideas to the table

and rallies support. The challenge now is to sustain that momentum. Domestic reforms must be consistent,

diplomatic tools must be sharpened, and alliances with like-minded states must be cultivated — not for the

sake of appearances but to amplify Indonesia’s voice when it matters most.

The Indonesian case suggests the promises and pitfalls of middle power statecraft that seeks to avoid

dealing directly with the source of geopolitical uncertainties — the strategic competition between the

United States and China. Rather than viewing its middle power status as a strategic buffer from great power

rivalry, policymakers should see it as an asset. Indonesia is large and influential enough that the United

States and China cannot ignore it should they choose to engage and help shape the relationship between

the two superpowers. That requires addressing domestic structural challenges and developing a deliberate

policymaking ecosystem to execute long-term strategies, even when the costs of action seem high.

If middle powers like Indonesia do not assert themselves and take greater responsibility — including pushing

back on the United States and China while providing them an off-ramp to collaborate — then there is more

reason for Washington and Beijing to view them through the prism of their own interests. Rather than seeing

middle powers as targets of influence or proxies in their competition, the United States and China should

view them as partners in shaping the broader regional and global environment for the greater good. For

Indonesia and other middle powers, all these considerations begin by acknowledging that they cannot ignore

the U.S.-China competition and should start developing long-term strategies, backed by solid reforms, to

tackle the problem head on. Standing by will only lead to the world passing the middle powers by.

Statements and views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors and do not imply

endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and

International Affairs.