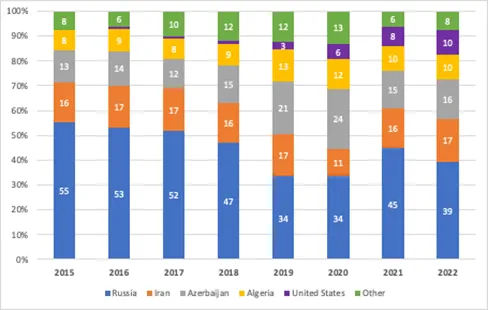

Turkey’s energy dependence on Russia poses both economic and security risks for the country, placing a heavy burden on its large current account deficit. Nevertheless, Turkey has deepened energy cooperation with Russia by allowing Russia’s Rosatom State Atomic Energy Corporation to build, own, and operate the Akkuyu nuclear power plant in Mersin, on the country’s Mediterranean coast. The first fuel was delivered in April 2023, during Erdoğan’s election campaign, and the plant was expected to be fully operational by 2026. However, considerable delays are now expected, given that German export regulations — possibly linked to sanctions — have prevented the delivery of key equipment, which the Russians later had to purchase from China.

As of 2025, Turkey is in further talks with the United States and South Korea to build a second nuclear power plant in Sinop, in Turkey’s Black Sea region. Turkey is also negotiating with China to construct a third nuclear power plant in the Thrace region, in the country’s northeast. In May 2024, the Turkish minister of energy declared that both sides were very close to a deal, with no concrete deal reached as of writing. The United States also entered discussions more recently, on the construction of both large-scale nuclear power plants and small modular reactors. While there are no concrete projects so far, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding to deepen their partnership in nuclear energy in September 2025. Plans are also underway for a new 10-year liquified natural gas (LNG) agreement with ExxonMobil to increase the weight of the United States in Turkey’s natural gas supplies.

Turkey is also diversifying its energy mix through renewable energy resources, particularly wind and solar. It ranks 11th globally and fifth in Europe in renewable energy-based power capacity. The government has also included hydrogen in its national energy strategy to help its decarbonization efforts. As of 2025, renewable energy sources constitute almost 20% of Turkey’s total energy mix. Despite the official commitment to increase renewables, there are significant hurdles, such as deficiencies in infrastructure, limited financial resources, regulatory barriers, and the slow pace of renewable energy auctions that hinder private investment. Furthermore, Turkey’s heavy reliance on natural gas for baseline power also slows the transition, preventing Turkey from realizing its potential as a regional leader in clean energy development.

On climate change, Turkey’s official position is not one of denial. In fact, the country has adopted a policy structure to address climate change, including a national long-term Climate Change Strategy and a National Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Plan (2024-2030). Turkey ratified the Paris Agreement in 2021 and announced its net-zero emissions target for 2053. Europe’s green transition, in particular the EU’s Emissions Trading System and its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, have been key drivers of Turkey’s climate agenda, given their potentially adverse impact on Turkey’s carbon-intensive industries, such as steel and cement, which are exported in large volumes to the EU. To mitigate these impacts, a Climate Law establishing a Turkish Emission Trading System was drafted in 2025, but it was withdrawn before the parliamentary vote in May due to opposition from climate change doubters on the fringes of the Islamist political spectrum. The draft law is expected to be reintroduced for parliamentary approval in the future. Still, Turkey’s climate efforts continue to face multiple problems at the implementation level, including its embedded infrastructure, limited financial resources, and a deep industry reliance on fossil fuels.

In addition to domestic sources, Turkey has traditionally resorted to Western funding, mostly from Europe, to finance its energy transition and climate adaptation. In fact, Turkey is the seventh top destination for European foreign investment in renewables. More recently, China has become more actively involved in financing and investing in renewable energy projects in Turkey. For instance, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank committed $5 billion to support Turkey’s climate resilience and sustainable development projects from 2025 to 2027. Still, Chinese investment in this field remains low, at only 1.21% of all installed wind capacity, largely because Chinese-backed consortiums to build large-scale wind and solar plants in Turkey have been sidelined in past bidding processes in favor of crony investors. This has led Chinese investors to cooperate instead with small and medium-size Turkish firms.

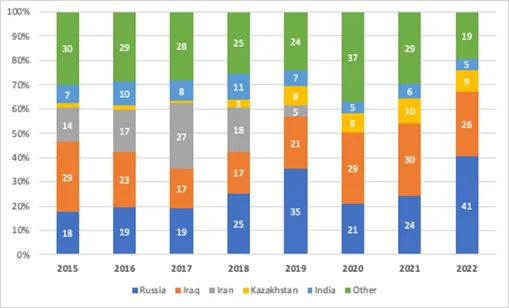

In contrast to their declared climate agenda, Turkish policymakers also wish to leverage the country’s geographic position to make it a regional natural gas hub. Turkey is already connected to Azerbaijan and Iraq via two oil pipelines and to Azerbaijan, Iran, and Russia via four natural gas pipelines. TANAP (Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline) and TurkStream already transmit supplies from the Caspian and Russia to the European markets, though the amounts only meet a fraction of Europe’s energy needs. Turkey expects that by diversifying its energy mix, it can send a considerable portion of imported natural gas to Europe. This, however, is easier said than done, given the financial, logistical, and political difficulties of securing sizable alternative energy supplies to replace those from Russia, which European states are keen to avoid. For instance, Iraq has large, untapped energy reserves that could potentially be transported to Europe via Turkey. The challenge is not only that the gas is highly toxic and therefore more expensive to extract but also that its export requires delicate political agreements, not least between the Iraqi Central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), as well as between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KPD) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Another complicating factor is the EU’s green transition, which will likely reduce future need for fossil fuels, making it necessary for Turkey to accelerate its own energy transition, possibly with European investments. Still, as of today, it can be argued that the fall of Assad and a weakened Russia and Iran in the broader region foster a more favorable international context for Turkey to serve as an energy hub, as demonstrated in the February 2025 agreement between Turkey and Turkmenistan to transport Turkmen gas to Europe via Iran’s existing natural gas network.

Technology

Turkey can be considered a moderately technologically capable middle power, ranked as an “advanced” country in mobile connectivity, with a burgeoning IT and digital services industry. The country has even been called a “star of European tech,” due to the global success of its startups and its young, technology-savvy population, making it an attractive market for investors. Nonetheless, progress in the technology field has been uneven, owing to the deterioration of industrial policy management, institutional weakness, and macroeconomic instability, particularly following the introduction of the authoritarian presidential system, which eroded and continues to undermine state capacity in Turkey.

Much of Turkey’s technological growth in recent years has been driven by its home-grown defense industry. Here too, however, the bulk of investment comes from Europe and the United States, with China and Russia playing relatively marginal roles. As a NATO member state, Turkey produces military equipment that largely complies with NATO standards and participates in defense technology trade, exchange, and collaboration with the United States and other NATO members. This limits opportunities for closer engagement with China and Russia on defense technology matters. Had Turkey’s relations with the West been more positive in recent years, it might have leveraged “friend-shoring” or “near-shoring” policies to attract investments in high-technology manufacturing.

U.S. and China Ties

Turkey’s strategy in the U.S.–China contest is selective alignment—maintaining a hedge between both sides while navigating significant economic, institutional, and geopolitical limits.

U.S. Ties

Turkish relations with the United States have been strained until recently, primarily due to U.S. financial and logistical support for the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in northern Syria, which Turkey considers a terrorist organization and an existential threat to its national security. The Turkish government’s mistrust toward Washington peaked after the failed coup attempt in July 2016. Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 Russian surface-to-air missile system in 2017 led to its removal from the United States’ F-35 fighter jet program and sanctions under the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in 2020, including a ban on all U.S. export licenses and authorizations for the Turkish Secretariat for Defense Industries (SSB) and asset freezes and visa restrictions on its president and other SSB officers. Although Turkey’s approval of Sweden’s accession to NATO in January 2024 secured U.S. approval for the sale of F-16 warplanes to Turkey, this concession was overshadowed by the U.S. decision to extend F-35 warplane sales to Greece on the same day, as Turkey had hoped to buy up to 100 F-35s to modernize its air force.

Furthermore, anti-American sentiment remains high among the Turkish public and is actively encouraged by the government. In public opinion surveys conducted between 2018 and 2022, respondents consistently ranked the United States as the biggest threat to Turkey’s national security. From the perspective of the United States, the last decade of tensions has strengthened the perception that Turkey can no longer be considered a credible ally, though at the time of writing, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding the future of U.S.-Turkey relations under the Trump administration, with the potential for improvement. Erdoğan’s visit to Washington in October 2025 signaled potential cooperation in defense, aerospace, and energy (nuclear and LNG). There is also some alignment on broader foreign policy issues in Gaza and Syria, with Turkey acting as a mediator/guarantor for President Trump’s October 2025 Gaza ceasefire framework and the United States supporting the integration of SDF into post-Assad Syrian central/state institutions.

Given that the Turkish economy is still tightly coupled with Western — especially American — financial networks, the West continues to be Turkey’s main source of capital. However, as the Turkish government has frequently disagreed with its transatlantic allies on key geopolitical issues, Turkey has become more exposed to “weaponized interdependence.” For example, amid geopolitical turmoil with the United States in 2019, President Trump threatened to “destroy and obliterate” the Turkish economy. That conflict came just one year after a 40% drop in the value of the Turkish lira, in the middle of another political stalemate between the parties in 2018. Furthermore, President Trump raised tariffs on steel imports from Turkey up to 50% in the wake of Turkey’s Syria operation in 2019. The Volkswagen Group also suspended its $1.4 billion investment in Turkey’s Manisa region and later cancelled the project entirely in 2021, which the Turkish officials lamented as a “political” decision.

China Ties

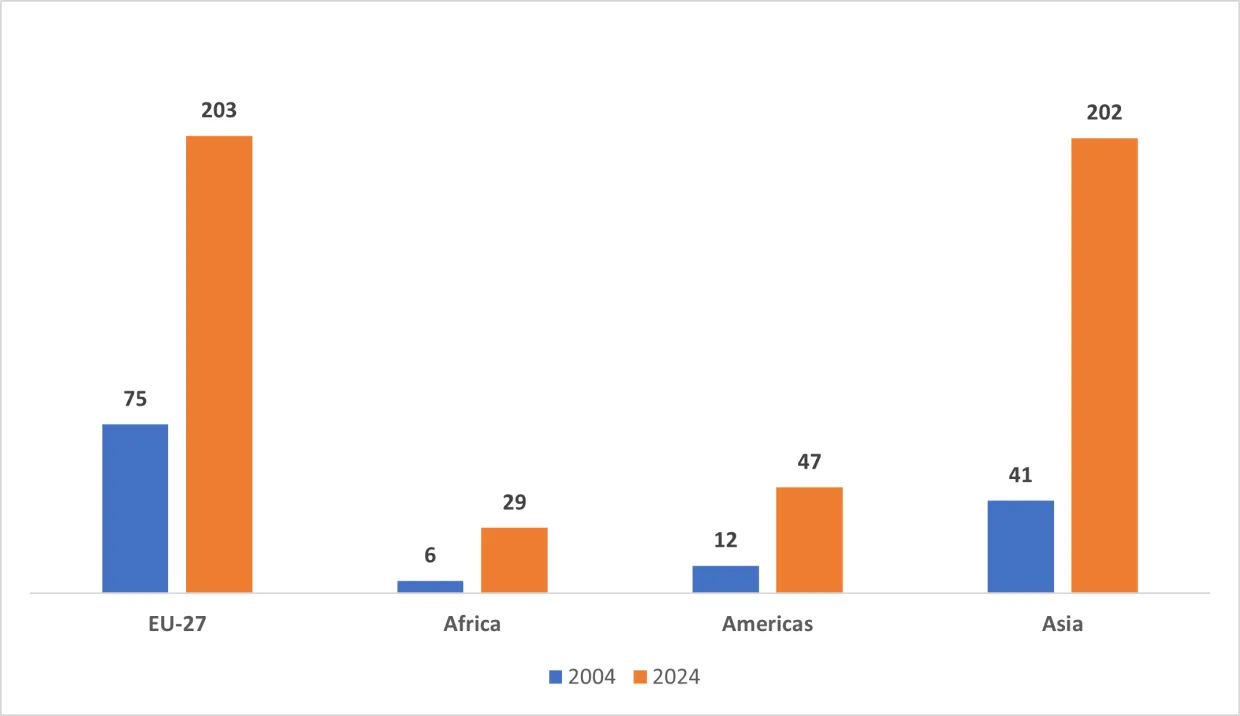

Turkey’s pursuit of autonomy from its Western allies has recently raised questions about its relations with China. After Erdoğan’s visit to China in April 2012, Turkey’s first high-level visit to China was by Minister of Foreign Affairs Hakan Fidan in June 2024. Although Turkey-China relations have progressed since the 2010 “strategic partnership” agreement, China has not yet emerged as a substitute for Turkey’s souring relations with the West. Factors include Turkey’s NATO membership, the negligible impact of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) on the Turkish economy, low Chinese foreign direct investment compared to flows from Europe and the United States, and Turkey’s trade deficit with China.

The Turkish government does not view China as a threat and seeks to deepen economic engagement, as Fidan expressed on his recent visit. Turkey joined the BRI in 2015 to attract Chinese investment, but it ranks only 23rd out of 80 countries that receive Chinese investment, totaling $9 billion by the end of 2023. Research suggests that Chinese investors have been reluctant to invest in Turkey due to the country’s weakened rule of law and unpredictable policies. Turkey also seeks to move closer to the Chinese technology ecosystem. China’s Huawei has held a dominant position in Turkey’s telecommunications sector for over a decade and is now expanding into the country’s renewables industry.

Turkey’s trade deficit with China is also striking. Turkey imports $45 billion in Chinese goods but exports only $3.3 billion. Turkey also disagrees with China on the state of the Uyghur minority in China and competes with it for influence in Africa and Central Asia. On September 2, 2024, Bloomberg reported that Turkey applied to join BRICS, although the outcome is still uncertain. The Turkish foreign minister later confirmed Turkey’s interest in BRICS membership and argued that “had Turkey been a member of the EU, it would not be in such a search.”While disillusionment with the EU is one factor, Turkey’s BRICS application also stems from a desire to forge closer economic relations with the Global South, attract more investments from China, and strengthen leverage against the West.

Some of China’s biggest technology companies, such as Xiaomi and OPPO, have built manufacturing plants in Turkey. In 2024, China’s BYD signed a $1 billion deal to build an EV manufacturing plant, giving it access to the EU car market thanks to Turkey’s proximity to the EU and the EU-Turkey Customs Union agreement. This investment also bears the potential to increase Turkey’s dependence on China-centered supply chains, which are shaped by major companies like BYD. Turkey’s position in the United States-China technology competition will largely depend on whether it deepens its technology-related cooperation with European states. As of now, Turkish technology regulations draw mainly from EU regulations, hinting at a potential space for deepened cooperation with its European partners. However, these regulations constrain the activities of big technology companies, running the risk of straining relations with the United States under the Trump administration. There is also the possibility of increased engagement with China in the technology space, especially if European investment is not forthcoming.

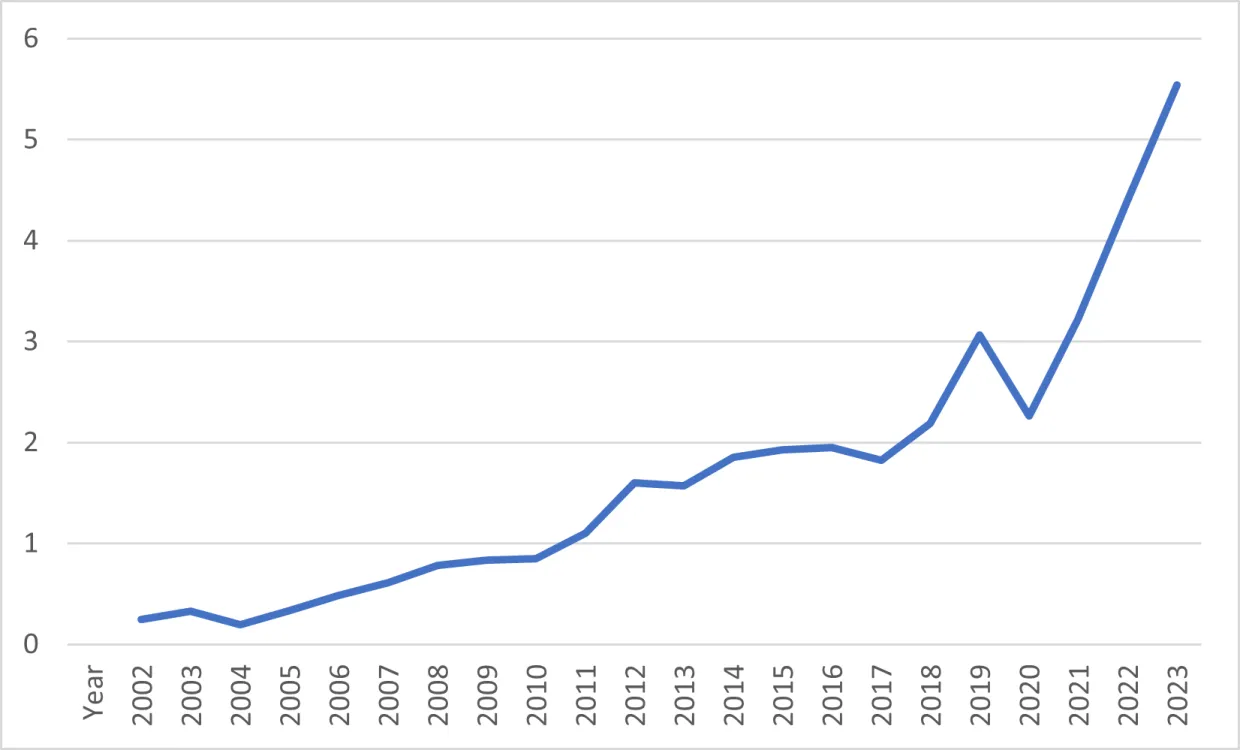

More recently, Turkey sees an opportunity in the Middle Corridor, a transport route connecting Turkey to China through the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and Central Asia. While this idea dates back to the fall of the Soviet Union and the independence of the Central Asian republics, there has been a surge of interest following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted the Northern Corridor connecting Europe to China via Russia and reduced China-EU shipments by 40%. Turkey is now involved in various initiatives to resolve the logistical problems associated with the Middle Corridor, including building an integrated rail and shipping network. Central Asian countries seeking to diversify from Russia and China welcome increased Turkish involvement in the region as well as the Middle Corridor initiative, which has the potential to boost trade and connectivity. Turkey already ranks among the top four trade partners of all Central Asian states, is a major arms exporter, and is among the top 10 investors in the region. Turkey also argues that the Middle Corridor can be integrated into the BRI, though the Turkish business community remains skeptical given the trade deficit with China and limited Chinese investment.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Like many middle powers in the changing international order, Turkey seeks strategic autonomy. In Turkey’s case, this means that its traditional Western orientation, rooted in the establishment of the Turkish Republic, is no longer the primary anchor for foreign policy. Instead, Turkey is working to diversify its options by forging closer ties with the Global South and China. Yet, as this report suggests, there are significant structural, ideological, and institutional constraints that limit how Turkey can achieve this.

One key structural constraint is Turkey’s lack of the political-economic fundamentals needed to effectively operationalize an autonomous foreign policy. Its deficit-led economic growth model has fostered dependence on the import of intermediary goods and advanced technology, a trend that continues in the absence of an effective industrial policy. Furthermore, the structure of Turkey’s external trade relations requires a carefully formulated multidimensional outlook to manage multiple dependencies. Its most important non-Western trade partners, Russia and China, are not large export markets for Turkish entrepreneurs, leading to a highly asymmetric relationship that widens Turkey’s current account deficit.

These structural limitations are compounded by ideological and institutional constraints that relate to Turkey’s domestic governance. Turkey is ruled by a populist authoritarian government that has pursued a largely anti-Western agenda both at home and abroad. The nature of the regime implies highly centralized decision-making with minimal checks and balances, eroding institutional and state capacity. This has discouraged investment not only from the West but also from China. Furthermore, foreign policy has been used mainly as a tool for regime security, fueling mistrust between Turkey and its European partners as well as the United States. This mistrust has weakened Turkey’s trade relations with the EU, which otherwise have the potential to offset some of Turkey’s structural political-economic constraints. It has also hampered security cooperation, as the EU has chosen to only selectively engage with Turkey on security and defense matters.

Finally, Turkey’s efforts to balance its Western and non-Western partnerships face institutional constraints related to its history. As a NATO member, its efforts to diversify its security and defense partnerships beyond the West face certain limitations, not least in the technology realm. Similarly, its Customs Union agreement with the EU, though in a need of an upgrade, ensures that the EU remains Turkey’s largest trading partner and a critical counterpart on climate regulation.

However, this final set of constraints can also be transformed into opportunities for the West in the broader competition with China. In all the policy fields discussed above, China only figures into three areas: a potential nuclear power plant construction agreement, an unlikely rare earth extraction agreement, and (so far) limited investment with some prospect for further cooperation in information and communication technologies. This suggests that there is still considerable scope for the West, and particularly the United States, to draw Turkey closer to the U.S. position on China. Turkey has the capacity to contribute to U.S. policies with its industrial know-how, reserves of critical materials, and growing presence in Africa and Central Asia — regions where it competes with China and where Western presence is not particularly strong. Stronger U.S. support for the Middle Corridor and energy cooperation could provide key avenues for this engagement. Responsibility does not rest solely with the United States, however. The EU also emerges as a key actor that can strengthen Turkey’s foothold in the West by opening talks to modernize the Customs Union agreement and by engaging with Turkey more closely on energy and security. Although China’s engagement with Turkey remains limited, the window for Western influence may not stay open long, as Turkey continues to pursue closer ties with China.

Yet much of the West’s hesitance, particularly in the EU, stems from lingering mistrust based in foreign policy spats that are closely linked to Turkey’s regime dynamics, such as its purchase of S-400s from Russia or its 2022-23 veto of Swedish and Finnish accession to NATO. Attaining regime security through foreign policy erodes long-term reliability and increases foreign policy volatility, making long-term coordination riskier. Although President Trump and his administration have been accommodating toward the regime, Turkey’s return to democracy and the rule of law should remain a key foreign policy priority in the long-term U.S. policy toward the country.